Learning, gathering knowledge, insight, awareness (however you want to think about it) is not linear. There are sources that suggest it is. In the early 1900s Harvard produced a fifty-one volume set of the Great Books, now available for free on Project Gutenberg. According to Charles Eliot, the man who collected these 51 volumes, you can read 15 minutes a day and get a liberal education. Think of the self-improvement!

This idea of self-discipline and self-mastery at the heart of education is steeped in so many assumptions about what knowledge is and whose observations gets treated as such that I just can’t. Though I totally admit to there having been a time in my life when reading all of those books and attaining that mastery was really important to me. So I started reading.

Unfortunately, the 51 volumes start with the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, which I’d already read but felt like I should read again to be thorough. His autobiography is based on the idea of a self-made man who can, through education and perseverance, shape himself into an ideal citizen. It was a source of Protestant inspiration for a century, but is now mostly a straw man used to exhibit privilege and self-promotion. I mean, he wheeled his books around in a wheelbarrow so people could see how industrious he was.

It is telling that Eliot begins with Franklin because both treat education, and life, as a to-do list of tasks that, once completed, entitle you to speak with authority. As long as you read the right books or get the right to-do list.

For people outside of traditional academic/social circles of power, these kinds of lists can feed into the imposter syndrome that makes them feel like they don’t belong, or to believe that they can only belong once they fill in all of the “gaps” in their knowledge and experience.

But the lists create the gaps.

There is no to-do list for gathering knowledge and no list of “Books to read before you die” that will ensure that you read the book you need to read when you need to read it.

You have to make your own list. Which is what I’m doing here. This is a list of what I’m reading right now, what it means to me, how it connects with what I’ve already read, or want to read, or learn. I’m the only one who can write it. Just as you are the only one who can write yours.

Here are a few tips for doing that:

Ask for recommendations from people you trust. Professors are always a good place to start, particularly if they’ve had a chance to get to know what you like to read and think about.

It’s okay to ignore recommendations, or to stop reading. Life is short. There is no shortage of stories.

Sometimes books will lead you to the next book. Follow.

Attend to serendipity. If a book or a song or movie keeps coming up, that’s a sign that it might be the book for you.

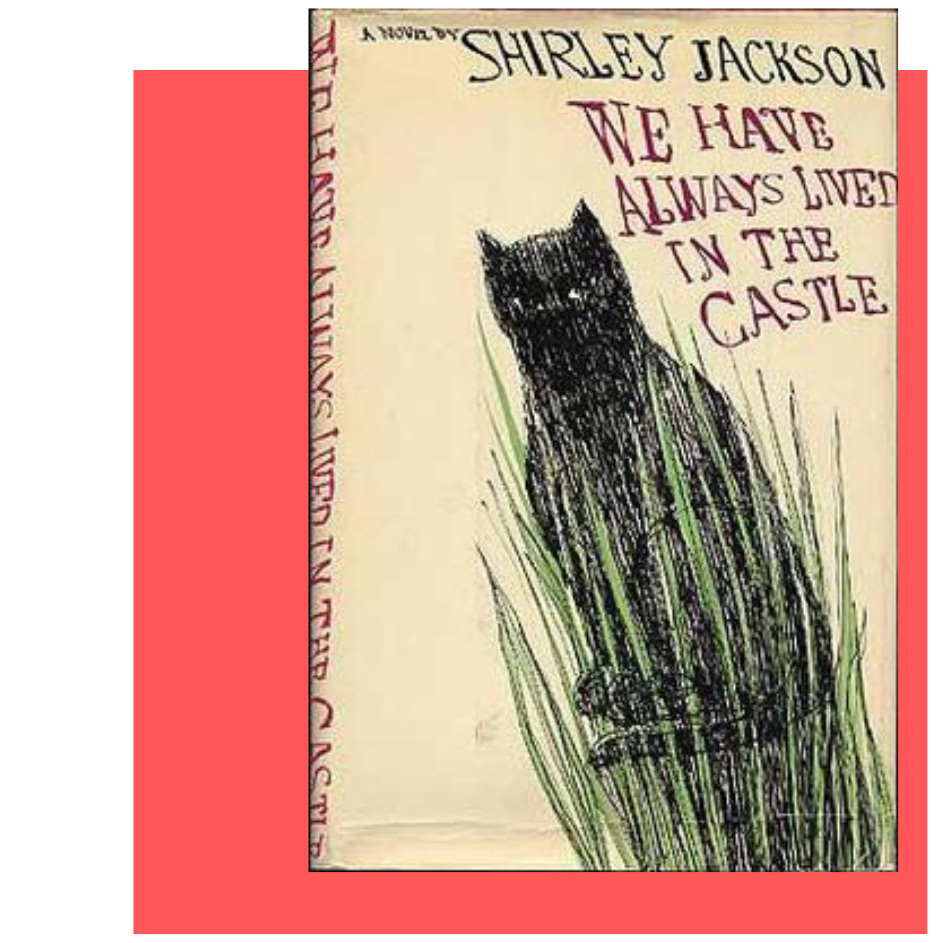

We Have Always Lived in the Castle was one of those books for me. I’ve taught Shirley Jackson’s famous story “The Lottery” probably for as long as I’ve taught. In the past few years, I’ve paired it with a South Park episode which uses Jackson’s set-up as a lens for looking at celebrity culture in America with a focus on Britney Spears. So when I read an article about this new edition of Jackson’s novel, I filed it away.

Then, on a road trip across the country, I found it on a friend’s shelf in Chicago. I couldn’t put it down. I considered stealing it. My friend was out of town, she wouldn’t notice. Or, she’s one of my best friends, so she’d understand. But I decided to pick it up at my favorite bookstore in Buffalo once we arrived, and then I could barely put it down for long enough to get to my sister’s wedding.

One more tip:

You’re going to connect what you read/see/hear/experience to other things. Make those connections vivid and material. I often process my reading by writing in academic prose. But I also do it in poetry, collage, and fiction. And in my teaching where I’m constantly searching for works that will engender real responses from my students that they cannot help but express. Here’s what this writing might look like:

Like “The Lottery,” We Have Always Lived in the Castle mines the tensions of small town life to explore how morality gets constructed and negotiated by communities comprised of very imperfect people. Like “The Lottery,” mob mentality and unreliable narration undermine our ability to separate people, and their acts, into good or evil.

Our narrator, a young woman who says she’s 18-years old but who seems much younger, or at least more innocent, begins her story well after the events that catalyze the rest of the tale: the death by poisoning of her entire family, and her sister’s trial for the crime.

Merricat and her sister attempt to live peacefully surrounded by people who think Constance killed her family, and the town’s righteous indignation intermittently erupts into grotesque acts of violent retribution. Gossip consolidates into myth, and the girls become the outsiders the rest of the community uses to define their goodness.

The people in the town behave abhorrently, while Merricat and Constance remain eerily calm. Only their Uncle Julian, the only other survivor, is troubled by guilt. He spends his days researching the case, poring over papers and files, but his inability to face the conclusions is manifest in literal dementia which, when it lifts, leaves him in terror. How can he live in a world, in a house, with the person who has killed his family? How do we make sense of it?

We don’t, Jackson suggests. It lives right below the surface in nursery rhymes and fantasy: a reality too unbearable to be real.