My friend and officemate is what Sarah Ahmed might call a “Thanksgiving Killjoy.” She’s not going to sidle up and nip into that green bean casserole without bringing up the 1621 “Thanksgiving” where the settler-colonists poisoned their native guests. Which is something I love about her.

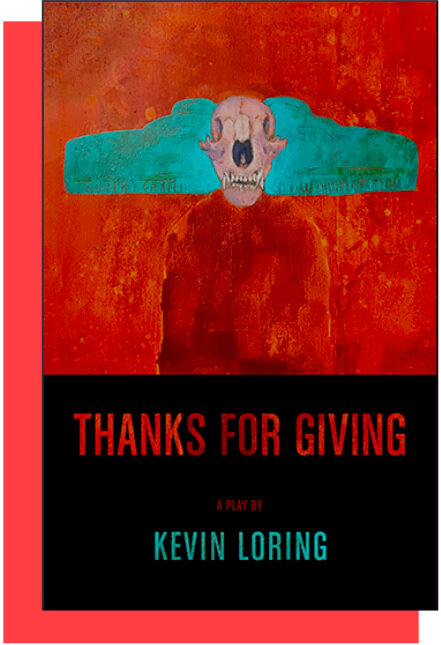

Kevin Loring’s play, Thanks for Giving, honors the need to have your turkey with truth serum. In it, an Indigenous family in Canada celebrates a fraught Thanksgiving. The title refers to First Nation’s people’s play on Thanksgiving that frames the colonists’ celebration as a thanks to them.

The play moves quickly, several years in three acts, so the dialogue is packed and polemical. One reviewer suggests that by trying to include every aspect of the indigenous experience the play is a bit much. But one year after Loring was named the Artistic Director of Indigenous Theatre at the National Arts Centre, “the first Indigenous Theatre Department of a National Theatre in the world,” the Canadian government pulled 3.2 million dollars of its funding.

If this play, right now is your only chance to tell your story, you’ve got to stuff it all in there.

To soften the didactic edge, Loring puts most of the teaching in the mouth of a college student home for Thanksgiving Break. Marie brought with her a girlfriend her family doesn’t know about, so she can’t help but lecture them on colonialism and false consciousness. She needs them to be woke.

“The history we are taught to celebrate,” she opines, “just glorifies the settlers and erases our struggles and experiences. It’s just a total trumped-up, bullshit colonial narrative that serves to perpetuate the marginalization of Indigenous people and erase our history of continued existence on this continent (48)”

It’s a mouthful at the dinner table, but for someone who has just finished Intro to anything, it’s a matter of course. She also tells the story of colonists kicking “the heads of Indians they killed through the streets like soccer balls” (44), a story I picture Jean telling at her next Thanksgiving.

If Marie is the play’s “Thanksgiving Killjoy” trying to protect the native past and perpetuate it into the future, her grandmother Nan is a living artifact of that past. As a girl she was taken to a re-location school, a brutal system of residential schools where native children were brutally cleansed of their heritage.

In some ways, the generational dynamic between Marie and Nan is universal, and Thanks for Giving is a very traditional Thanksgiving story: a grandmother gathers her family around the table with her ornery husband (Clifford, a white man), upstart grandchildren home from college or the military with new partners and ideas, too much drinking, and too much past, unspoken and hauntingly present.

Except that the play starts with a stylized invocation to the Bear Dancer, a mythical figure, interrupted by a gunshot, and the play’s narrative. Clifford has killed a grizzly bear, an animal sacred to Nan’s people, and for the rest of the play its carcass hangs over the stage, a grotesque physical reminder of the violent past. Is that too much for one play?

Or is it just enough?