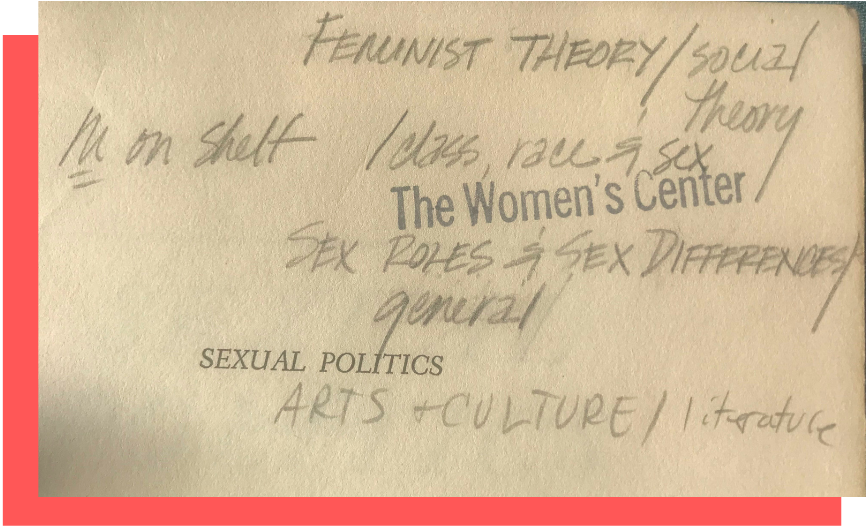

Something I read as part of the Almodóvar project mentioned Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, so the last time I was in Buffalo I picked it up from the bookshelf my mom still keeps for me at home (thanks, Mom). My copy comes from the Barnard Center for Research on Women library. The Center’s idiosyncratic indexing categories are hand-written on the inside cover in Allison’s neat handwriting. I worked there in the late 90’s, and we were beginning to move toward internet technology instead of print journals and books, and our amazing ephemeral files (an actual copy of the SCUM Manifesto!) This was inevitable and way more efficient than clipping articles related to women from the NY Times, but still sad. Like the Lesbian Herstory Archives, which has also entered the digital age (sort of), the miscellany and the handwriting shaped our ethos and epistemology.

But when they started unloading books, I grabbed a bunch, including Sexual Politics, because she has a chapter on Jean Genet. My high school theater instructor, Toni Smith Wilson, introduced me to him because she thought his writing and sensibility (sainthood through sin!) were right up my alley. Because of the nature of our relationship, I took that as a compliment.

Allison (right) with student workers and researchers in the Women’s Center before the internet was really a thing.

Sexual Politics was published in 1968, but it reads like a deposition in a Harvey Weinstein trial. Kate Millett was looking at the representation of sexual violence against women and the feminine and the way it registered larger attitudes and practices within the culture. And she was pissed.

In some ways this can also be said of Audre Lorde or Virginia Woolf or Mary Wolstonecraft or Victoria Woodhull. The same themes are repeated throughout what we think of as Feminist Criticism, though each era has its particular focus. Is this teleology or eternal recurrence? Are we able to make these arguments because we’re standing on the shoulders of giants? Or do we fight the same battles over and over because we are incapable of learning from our monstrous past?

Unlike me, Millett focuses only on male writers. Do you like D.H. Lawrence (I thought I did), Norman Mailer (I didn’t particularly care for him, but I didn’t loathe him like I do now), Henry Miller (I did. I really did? Yes, I’ve gone to his library every time I’ve visited Big Sur)? You probably won’t after reading this. Her treatment of Genet is kinder, but this seems to be because he identified as a passive homosexual and portrayed the marginalized with care and reverence. This is the same reason Almodóvar gets a pass for his representations of sexual violence, and something that might be worth looking into - I love any reason to look back at Genet.

Millett’s strategy is to just quote from their works. The attitude toward women is predatory, contemptuous, and objectifying, if not entirely murderous. There is no intimacy in their graphic representations of sex and rape, only humiliation and dominance. Why were these men taken seriously, or given such a stage for their writing? I mean Mailer’s “poetry”? The lack of self-awareness is frightening.

In the case of the first three, Millett’s close readings are nauseating and prophylactic: she’s trying to protect us from something. Her irony in these chapters is biting. I love it:

“Since his mission is to inform “cunt” just how it’s ridiculed and despised in the men’s house, women perhaps owe Miller some gratitude for letting them know (309). ”

Before she gets into the close readings she does a very nice history of female revolution and the inevitable counter-revolutions in the U.S., and in Germany. The rise of fascism and similar turns toward authoritarian government are linked to the idea that female agency weakens Western culture. In this section, she ruins Ruskin for you. Though I love Ruskin, for some reason that one wasn’t as painful for me. Same for Hardy. It’s not like I didn’t know their work was problematic.

My work differs from hers in that I’m not going to give men the floor. I’m going to look at Weinstein through Almodóvar, but then I’m going to turn to women’s representation of these experiences. I’m not giving these outrageously misogynist images and ideas any more space, or any more air. People talk about cancel culture, but she’s not calling for these writers to be cancelled. She is just making it impossible for us to look at them, or the culture that centers their narratives, in the same way again. That’s what she meant by “sexual politics.” Is that what #Metoo means for us?